-

Don’t just do something. Stand there.

I’ve spent my entire life in and around Tornado Alley. When the BIG ONE comes up, your job is to hunker down and wait. Humans have a predisposition towards action. If there is a problem, yo, we want to solve it. But as I have more and more experiences in my life I’ve come to Continue reading

-

Good enough

I eat a McDonald’s breakfast sandwich several days a week. I can imagine a young line worker, trying to impress their boss, taking extra care to get that Sausage McGriddle right. I can also imagine that supervisor telling that young employee they need to step it up and get food out the window faster. We Continue reading

-

I think you will appreciate this

Gabe thinks the words “I thought you might like this” is an act of vulnerability. He’s right, but that’s not what a lot of people say. I can’t count the times I’ve been told “Landon, you will LOVE this.” Unless it’s my wife or close friends, I almost always do not like it. Even then, Continue reading

-

Why I like to argue about Die Hard

I have a recurring gag I turn to every year after Thanksgiving. As TV channels are promoting their winter holiday slate of movies and live events, I decide to be a bit of a Scrooge and I log onto various social media platforms, and I start the “Die Hard Debate” (DHD). I begin by laying Continue reading

-

“Stop What you’re Doing and Enjoy the Beauty” [Friday Photo]

![“Stop What you’re Doing and Enjoy the Beauty” [Friday Photo]](https://plgrm.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/05-stop-what-youre-doing-and-enjoy-the-beauty.jpg?w=1024)

Like a lot of you, I live in the suburbs. I never planned to live in the suburbs, nor, if I’m honest, did I want to. But when we moved cities a few years ago, we couldn’t find any houses we could afford in the urban core. So, here we are. I love it. It’s Continue reading

-

The Four Bs

(This is a post about religion, but I think it applies to all groups of people in one way or another.) When I was growing up, I was taught the most important thing about being a Christian was that I believed the right things. My mental acceptance of a set of principles defined my status Continue reading

-

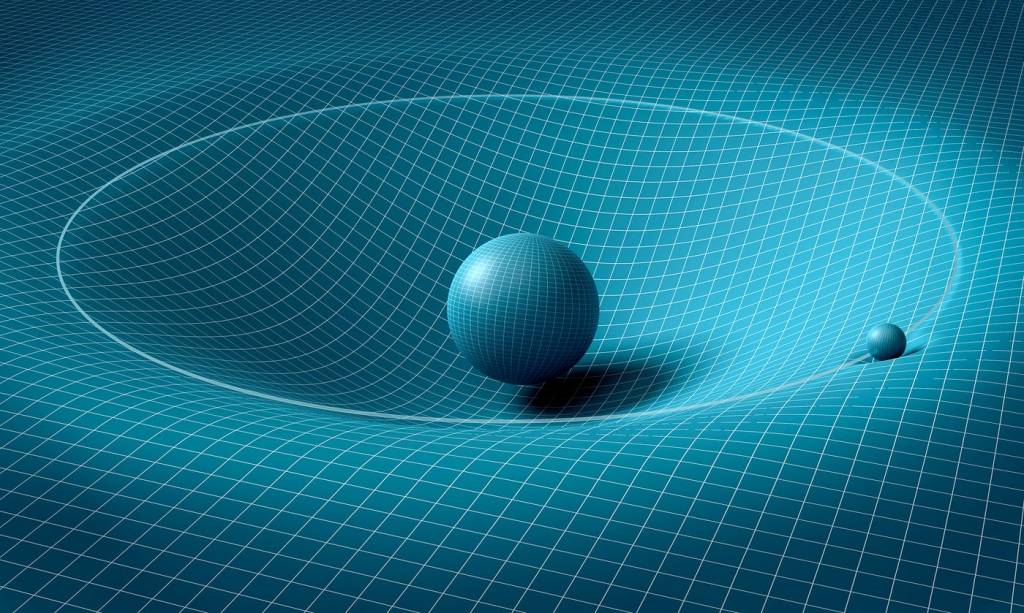

A Theory of Relativity

All things are relative, but some things are relatively better than others. Continue reading

-

Ants Marching

It is estimated there are 1 Million ants on Earth for every 1 person alive. I like to drop this fact when I point out that the more complex something is, the less of it there is. Conversely, the simpler something is, the more of it there is. Now, simple and complex is not analogous Continue reading

-

The Key to Curing Burnout

I’ve blogged about Sabbath before. I think about sabbath a lot. Especially as a Christian pastor, I think having a vibrant and well-formed understanding of sabbath is a key part of our faith. I’ve often attended to the systemic aspects of promoting Sabbath. As the leader of a church, a lot of what I do Continue reading

-

“The honeymoon is over”

“The honeymoon is over” is meant to be said as a bad thing. When we say it, we’re referencing that time at the beginning of every relationship when things are harmonious, when everything we do or attempt is free of problems. But then that’s all over. And now…well, it’s not the honeymoon anymore. Historian Susan Continue reading

About Me

My name is Landon Whitsitt. I live in Oklahoma City. I have a wife, four kids, and two dogs.

I’m a pastor and a speaker. I’m a writer and a thinker. I’m a photographer and musician.

the Schedule

New posts go up every Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday.